By Jack M. Forehand (@practicalquant) —

The investment management business has improved dramatically in the past twenty years.

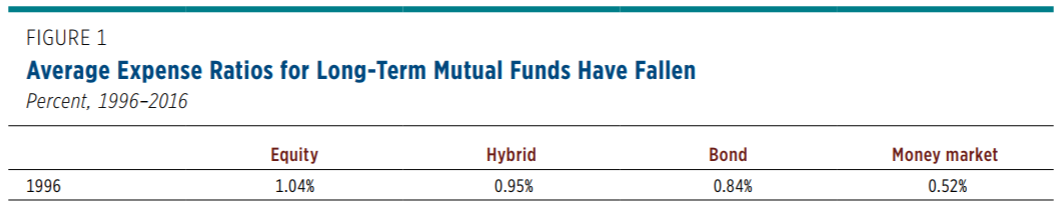

The days of brokers selling high priced products to unsuspecting consumers that serve no purpose other than to line their own pockets are mostly gone. Fees have also fallen drastically, and efforts to educate investors on them by people like John Bogle have led to substantially increased investment in index funds and other low-cost products, which is certainly a good thing. In 1996, the average equity mutual fund in the U.S. charged over 1%. Today the average is about 0.63%, a decline of nearly 40%.

Source: https://www.ici.org/pdf/per23-03.pdf

It used to be that selling products that were more built for profit than to benefit investors would secure your mansion in Greenwich. Now those mansions are being fire-sold. As it turns out, you actually need to add value to make money for investors – and, even then, you will make much less of it than back in the day.

In order to achieve investing fame, you once had to appear to have all the answers. Now, however, the best investment writers freely admit that they don’t have them. We have gone from a period where a pundit gained a following by picking stocks on television or making doomsday market calls to a new world where people like Barry Ritholtz, Josh Brown and Morgan Housel have become leading investing writers by doing what was unheard of ten years ago; telling people the truth.

Technology has also changed the investing landscape for the better. The ability to use computers to follow investment strategies with discipline and the identification of the factors that lead to market outperformance (and their deployment in a low-cost way), are both major positives for investors.

Our Biggest Area of Failure

So the investing world has experienced massive change for the better and things continue to improve every day.

But there is one area where all of us haven’t found the answers yet – getting investors to limit their emotions and make the right decisions.

It is a widely accepted truth that investors underperform the funds they invest in – the result of emotion getting the best of them, leading to buying and selling at mostly the wrong times. And despite all the improvements in investing, this really hasn’t changed.

There are certainly efforts being made in the area of investor behavior and psychology, but the “behavior gap” has been shown to adversely affect returns significantly more than fees, so there is no area where more benefit can accrue directly to investors than this one. But thus far, we haven’t made a major dent.

The reason comes down to the way we are wired as human beings. When we see the market going up, we tend to believe it will continue and we want to buy. When we see it going down, we see that continuing and want to sell. And the more extreme the market move, the more extreme the emotions get.

It is even worse for investors who use active managers. When those managers underperform for extended periods, which is inevitable with active management, we tend to bail on them at the worst time. When a fund is hot, we tend to pile our money in, again doing the opposite of what we should.

In a recent Masters in Business podcast interview , Barry Ritholtz interviews John Montgomery, the CEO of Bridgeway Capital, which manages $8.4 billion, who sums this up well. Montgomery uses the example of one of their more aggressive funds that has a strong long-term track record. Investors in the fund, he said, have only achieved two-thirds of its annual return, which means that over a 30-year period, the average investor would only realize one-third of the fund’s total return (if you factor in the effects of compounding) . So, if the fund was up 600% over 30 years, investors would only see gains of 200%, a huge problem for someone saving for retirement While fees have been the target of the media in recent years, and rightfully so, they have a much smaller impact than that, and the Bridgeway fund is in no way unique in this respect. The same thing happens with most funds and investment strategies.

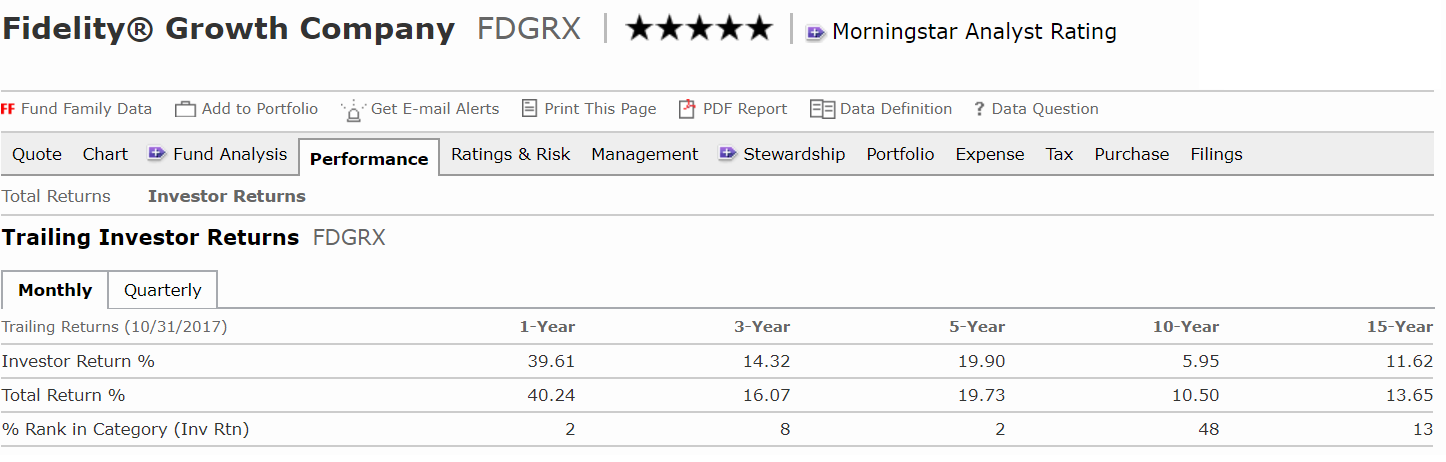

The image below, taken from Morningstar, shows the returns of the Fidelity Growth Company fund, one of the best performing large cap stock funds over the last 20 years (as of Oct. 31st, 2017) according to Kiplingers. The chart, which compares investor returns to total fund returns, shows that over the last 15 years, investors in the fund have achieved a return of 11.6% versus 13.7% for the fund. On a 10-year basis, the fund has returned a solid 10.5% per annum, but investors have only achieved 6.0% a year on their investment. In fairness, some of Vanguard’s funds have higher investor returns than actual fund returns (as Ben Carlson wrote about here in 2015), but in most cases the investor return is far below the return of the fund itself.

There is a tendency for all of us in the investment industry to focus on our published returns, but it’s important to recognize that those returns are meaningless if investors don’t stick with our strategies to get them. Sometimes, therefore, we need to sacrifice some long-term returns to develop a strategy clients will stick with. In a perfect world, we would be able to pursue the best returns regardless of volatility, and clients would stay the course in order to realize those returns. Unfortunately, that perfect world doesn’t exist.

Looking for a Solution

So, how do we fix all of this?

Unfortunately, there is no easy answer. The best strategy is to make gradual, incremental improvements in the hope of getting long-term results. While automation and computing power has improved many areas of investment management, it doesn’t offer a complete solution. Why? Because there is always a person whose money is on the line sitting behind all of that, and that person is likely to panic when faced with losing their money. They will never outsource decision-making to a computer in times of panic.

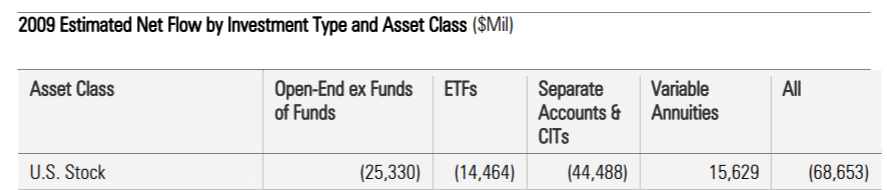

The chart below shows U.S. Stock outflows in 2009, which ended up being the year the bear market ended (the S&P 500 finished the year with a 20%+ gain). As you would expect at a market bottom, where fear is at its peak, investors continued to pull money out of equity funds in droves, doing exactly the wrong thing at the wrong time. Since January 1, 2009, the market has enjoyed a cumulative gain of 244%, confirming that the decision was a decidedly poor one.

Source: http://morningstardirect.morningstar.com/clientcomm/2009.pdf

At the end of the day, I think investor education is the best defense. Those of us that work in the business need to continue to write and speak about this topic as much as possible. We need to make more investors aware of these biases and how much they affect their potential to achieve their long-term goals.

That said, education alone isn’t enough. It is also crucial that investment professionals present clients with a long-term perspective to make them understand that the panic they feel today will be seen in a very different context ten years down the road, and the decisions they make now will determine whether they reach their long-term objectives.

And gentle nudges can help here too. For example, Betterment found that when you present clients with the tax consequences of selling an investment on the confirmation screen before they finalize a trade, many people will rethink the sell decision, thus avoiding some emotional reactions. Advisors who don’t use automated solutions can also take advantage of this by presenting clients with the tax consequences before they act, which we have found works very well and limits unnecessary trading.

We also need to talk to our clients more to build knowledge and trust, which is especially important during market panics when many advisors tend to avoid talking to their clients.

In addition to the work of advisors, investors should also put as many barriers between themselves and emotional decisions as possible. For example, investors should never invest money that they might need in the near term, so they won’t panic when the inevitable decline comes. They should check their account balances as infrequently as possible, especially during market declines, and should never fall victim to thinking they can call market tops and bottoms. This will only destroy long-term returns.

In the end, there is no magic bullet here. Rather, it is an incremental process where both investors and investment managers need to educate themselves and try to maintain a long-term focus. In some ways, it is astonishing to me we haven’t made more progress, since this issue has been known for a long time. But in other ways it isn’t, since this problem is a function of the way we are wired as human beings, which can’t be changed. Now that we have gotten a lot of the low hanging fruit out of the way by fixing the obvious bad and self-interested behavior in the industry, I think this is our biggest area of need to help clients achieve their long-term goals. Hopefully the next decade will be a much more productive one in resolving it than the last one was.

——

Jack Forehand is Co-Founder and President at Validea Capital. He is also a partner at Validea.com and co-authored “The Guru Investor: How to Beat the Market Using History’s Best Investment Strategies”. Jack holds the Chartered Financial Analyst designation from the CFA Institute. Follow him on Twitter at @practicalquant.