In a sign of the changing times, tech giant Meta Platforms was bumped into the value stock benchmark Russell 1000 Value Index as a result to lowered earnings growth. While its change in status can be attributed to internal issues and a shift in strategy, it’s also an example of how the previous definitions of value have changed, reports an article in Chief Investment Officer.

Value indexes now face stiffer competition as more high-flying stocks tumble down into their ranks. Market volatility as well as lower interest rates, more debt, and slowed economic growth have also contributed to the shift, the article contends.

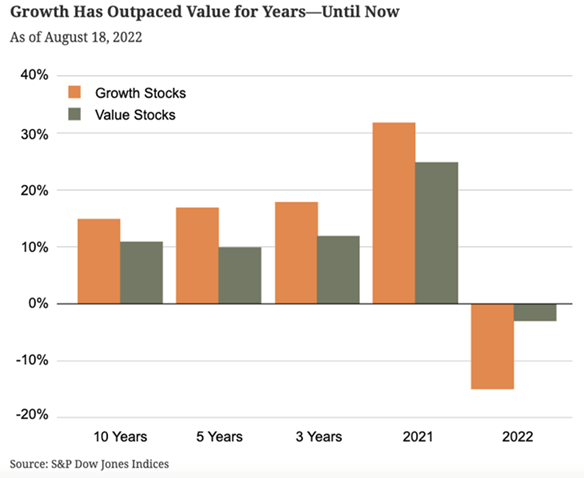

The traditional definition of value stocks maintains that they’re priced lower than what they’re truly worth thanks to investor sentiment, as opposed to growth which generally shows rapid expansion and popularity with investors. And though value had its heyday for decades, growth has dominated the field since before the dot-com burst, with very few interruptions. Last year, as the economy rebounded after the onset of the pandemic, growth logged in at 31.2% while value lagged behind at 24.7%. But the Russell 3000 Growth Index was decidedly top-heavy with tech stocks like Meta, so when the tech bubble burst, it was bound to topple over. Geopolitical tensions and macroeconomic turmoil also fueled value’s comeback, which tends to outperform during bear markets, recessions, and periods of surging inflation. All of that has created a perfect storm for value to rise, and growth to fall.

Value investors used to have the field to themselves, but in the past few years more people have been getting in on the action, such as hedge funds and quant funds, the article maintains; indeed, hedge funds doubled assets between 2008 and 2015. Years of low rates has fostered larger debt loads, and there have been less public companies which makes for a tighter playing field. But while many well-known value investors are heralding this as a new “golden age,” the article notes that value investing can be tricky. It involves extensive research, and often having the wherewithal to go against the grain when the consensus on a particular stock is different than your own. And many managers incorporate both value and growth into their long-term strategies.

It’s also easy to fall into a value trap, the article warns, where investors are lured in by a cheap share price and a few decent metrics and wind up with a losing investment. The article highlights the clothing retailer Gap as an example of a value trap: it held a P/E of 8 in 2019 and appeared to rebound after Covid lockdowns eased, but has now dropped and is unprofitable. Likewise, Meta could be considered a value trap; its fundamental business is down and it’s shelling out $10 billion to expand into the metaverse—a move that is anything but assured. But worthy value investments are out there for those skillful investors who take the time to look.