By Jack Forehand, CFA (@practicalquant)

“Importantly, reversion to the mean in the investment business extends well beyond the results for mutual funds. It applies to classifications within the market (small capitalization versus large capitalization, or value versus growth), across asset classes (bonds versus stocks) and spans geographic boundaries (U.S. versus non-U.S.). There are few corners of the investment business where reversion to the mean does not hold sway.” – Michael Mauboussin

Mean reversion is one of the most powerful forces in investing. Whether it be the performance of asset classes, the fundamentals of companies, or economic data, almost everything in investing will revert to long-term averages over time.

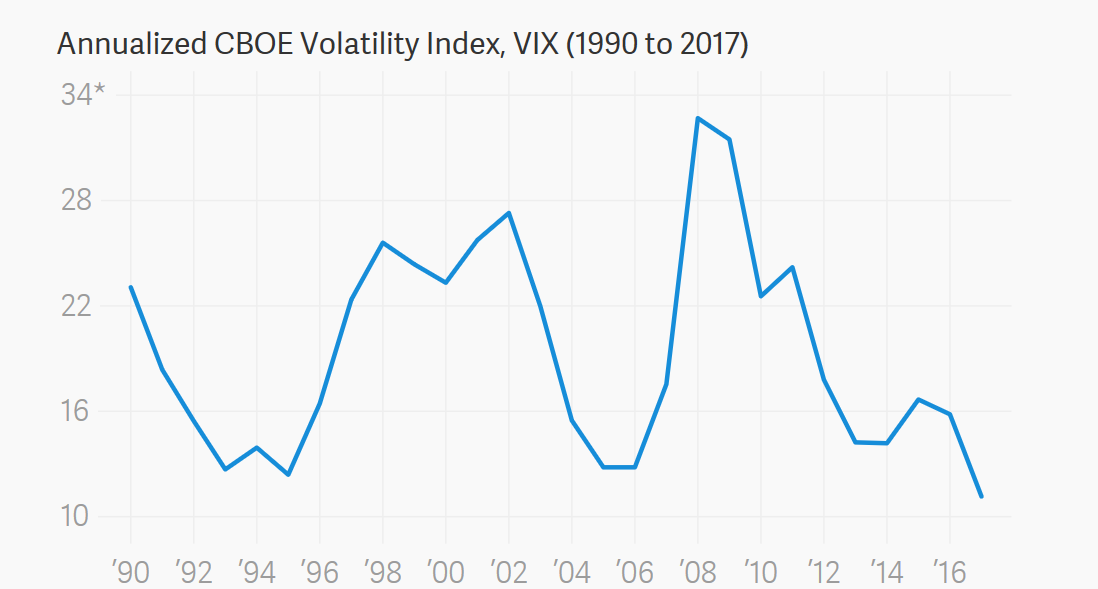

Despite the fact that 2017 was a very calm year for the market, behind the scenes it was actually a year of extremes in many ways. For example, that calmness itself was a very rare occurrence. By most measures, 2017 was the lowest volatility year we have had in decades. The average daily change in the S&P 500 for the year was the lowest it has been since the 1960s. And it was the first year ever where the S&P 500 was up for all twelve months.

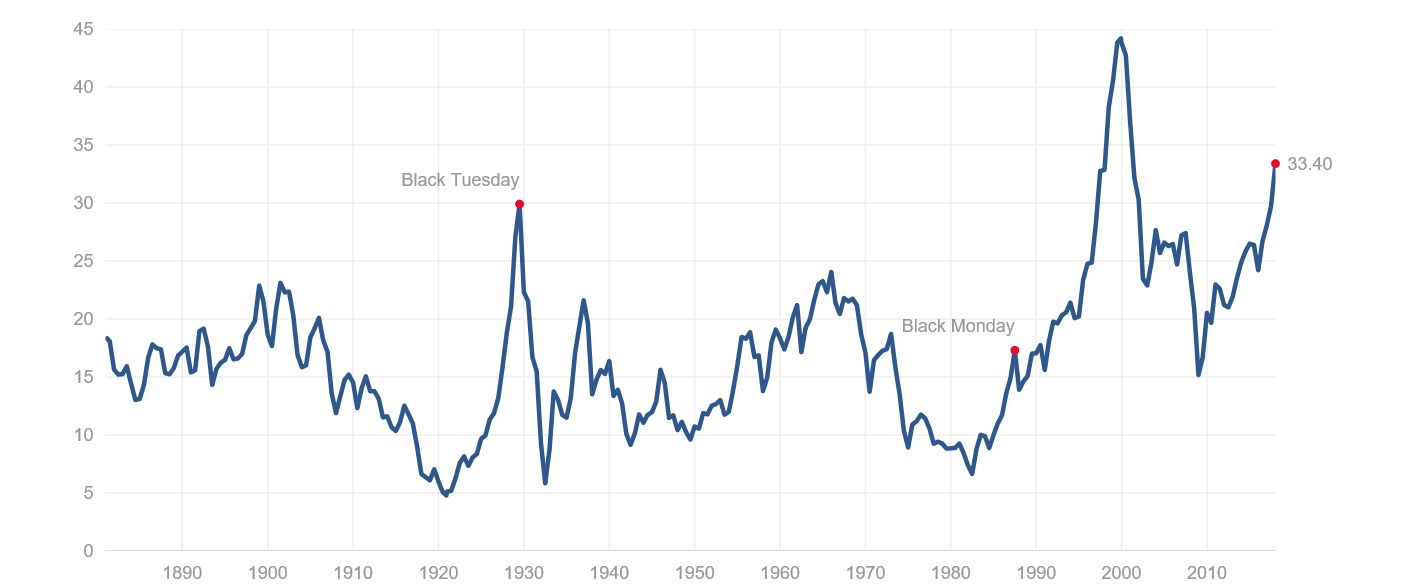

Valuations are another thing that by most measures are also at extreme levels. At its current level of around 33, the Shiller PE Ratio is higher than it has been at any time in history, with the exception of the 1990s tech bubble. Other valuation metrics also tell a similar story.

http://www.multpl.com/shiller-pe/

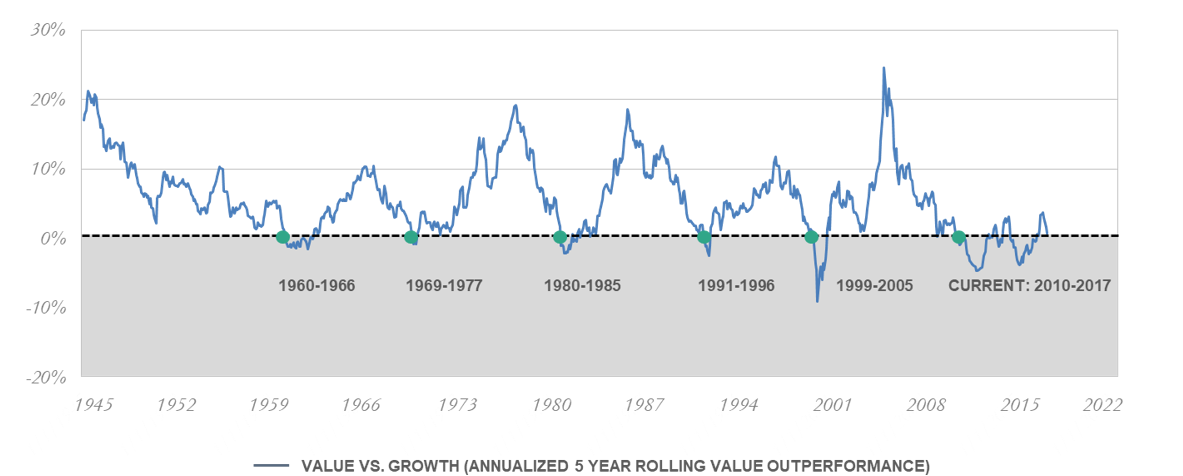

And the extremes don’t just apply to the market as a whole. The rotation among different types of stocks has also reached very rare levels. For example, value stocks are currently going through one of their worst performing periods in history. The performance spread between value and growth has twice reached levels it had never seen before, again with the same exception of the late 90s.

http://www.euclidean.com/market-environment/

So given that all these metrics have reached extreme levels, and given that they will likely revert to their long-term averages over time, the solution here seems quite simple: take positions that will benefit from a rise in volatility, short the market as a whole, and buy value stocks. That way when all those things go back to their long-term averages, you will make a killing.

The issue, of course, is that investing isn’t that simple. Although mean reversion is a very powerful concept, its implementation can be much more challenging.

The Importance of Timing

In investing, timing is everything. Being right about something, but being too early, is often indistinguishable from being wrong. And the timing of mean reversion is impossible to gauge.

So the three trends above are likely to all revert to their means, but they will likely take far longer than you think to do it, and investors that are early may have losses so great when that day arrives that they can’t recover.

To illustrate this, let’s look at each trend individually.

The CBOE Volatility Index (VIX) is a common way that investors measure volatility. If you look at the chart below, you will see confirmation of what we discussed above, which is that volatility is currently extremely low.

https://qz.com/1154499/the-vix-2017-was-the-least-volatile-year-in-decades/

But if you put yourself in the shoes in an investor looking at volatility at the end of 2016, you would have also drawn a similar conclusion. If you have used the VXX ETF, which tracks the VIX, to take that position, you would have lost about 72% of your money in 2017. To make that back, you would need to make almost 5x your money going forward.

That is an extreme example, but the same holds true for valuations. Look at the Shiller PE chart at the beginning of this article and picture yourself as an investor in stocks in 1997. At that point, the tech bubble hadn’t occurred, so you didn’t have any of the information to the right of 1997 in the chart. Based on what you saw at that time, the market was now exceeding its highest valuation ever. If you were betting on mean reversion, you would likely have placed your money in cash at valuation levels that looked that high. But the market went on to produce an annual return of over 20% for the next two and a half years before the bubble finally burst.

The same concept also applies to value stock underperformance. Value stocks look cheap today relative to growth stocks, but they have been underperforming growth stocks since 2007 and they have just continued to get cheaper. If you look at the value vs. growth chart above, in all the previous instances where growth exceed value over a 5 year period (the green dots), value outperformed growth by at least 50% within the next 5 years. We are now over six years in this cycle and it still hasn’t happened. So even if something is unprecedented in history, it can still happen. Value will eventually mean revert and outperform, and given the length and magnitude of the underperformance, the outperformance will likely be substantial, but there is no reason this underperformance can’t go on for years more until that happens.

There is Sometimes a New Normal

The other danger of betting on mean reversion is that sometimes the mean changes. The average Shiller PE Ratio of the S&P 500 is about 17 since 1900. But in the last 25 years it is 26. When something stays above its long-term average for that long, you have to ask yourself whether something has fundamentally changed to justify it. In this case, there are many factors that could justify a higher PE than the historical average. Technology has changed dramatically since 1900 and the net result of that has been more efficient businesses with higher profit margins. Accounting standards are also very different now than they were then. So comparing numbers from the two periods isn’t a fair comparison.

It is very possible that those expecting the Shiller PE to revert back to its long-term average will be waiting a very long time. That doesn’t mean that the much higher level of the past 25 years is the new mean either. It is very possible that new higher average is also deceiving, given that we have just been through a long period where valuations were well above average. The point is that in order to bet on reversion to a mean, you need to have an idea what that mean is, and averages do change over time. Figuring out whether a change in an average is something that is temporary, or part of a long-term fundamental shift, can be very difficult to do in advance.

Playing the Odds

All of this is not to say that mean reversion isn’t a dominant force. It is in fact one of the most powerful things in investing. The point is that playing mean reversion in practice is much more difficult than it looks in theory. Often times, for the reversion to take place there needs to be a catalyst of some type. A bear market, of course, will bring valuations down and increase volatility. Rising interest rates could make value stocks come back into favor. It’s impossible to predict what may cause these trends to reverse and mean reversion to take hold, but history would teach you that when the catalyst comes, the reversion can be significant.

Investing is a game of probabilities. When something deviates from its long-term averages, the probabilities are that it will eventually revert back to them. And the longer it deviates and the greater the magnitude of the deviation, the higher the probability of reversion is. But that probability is never 100%, no matter how long a trend goes on. It is important to understand that when you bet on mean reversion, you are likely to be early. And it takes patience and discipline to get to a point where you are eventually right. Only then can you realize its benefits.

Photo: Copyright: gopixa / 123RF Stock Photo

—-

Jack Forehand is Co-Founder and President at Validea Capital. He is also a partner at Validea.com and co-authored “The Guru Investor: How to Beat the Market Using History’s Best Investment Strategies”. Jack holds the Chartered Financial Analyst designation from the CFA Institute. Follow him on Twitter at @practicalquant.